5. What's in a View? A look at the alternatives

In this chapter, I will look at the concepts and differences of opinion between various frameworks when implementing views. I actually started writing this chapter with a code comparison (based on TodoMVC), but decided to remove it - the code you write is mostly very similar, while the underlying mechanisms and abstractions used are different.

The view layer is the most complex part of modern single page app frameworks. After all, this is the whole point of single page apps: make it easy to have awesomely rich and interactive views. As you will see, there are two general approaches to implementing the view layer: one is based around code, and the other is based around markup and having a fairly intricate templating system. These lead to different architectural choices.

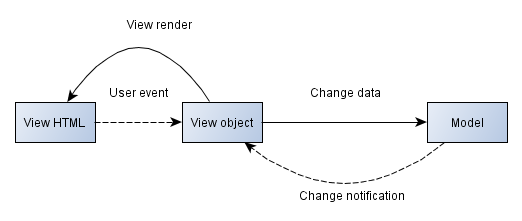

Views have several tasks to care of:

- Rendering a template. We need a way to take data, and map it / output it as HTML.

- Updating views in response to change events. When model data changes, we need to update the related view(s) to reflect the new data.

- Binding behavior to HTML via event handlers. When the user interacts with the view HTML, we need a way to trigger behavior (code).

The view layer implementation is expected to provide a standard mechanism or convention to perform these tasks. The diagram below shows how a view might interact with models and HTML while performing these tasks:

There are two questions:

- How should event handlers be bound to/unbound from HTML?

- At what granularity should data updates be performed?

Given the answers to those questions, you can determine how complex your view layer implementation needs to be, and what the output of your templating system should be.

One answer would be to say that event handlers are bound using DOM selectors and data updates "view-granular" (see below). That gives you something like Backbone.js. There are other answers.

In this chapter, I will present a kind of typology for looking at the choices that people have made in writing a view layer. The dimensions/contrasts I look at are:

- Low end interactivity vs. high end interactivity

- Close to server vs. close to client

- Markup-driven views vs. Model-backed views

- View-granular vs. element-granular vs. string-granular updates

- CSS-based vs. framework-generated event bindings

Low-end interactivity vs high-end interactivity

What is your use case? What are you designing your view layer for? I think there are two rough use cases for which you can cater:

|

Low-end interactivity

|

High-end interactivity

|

|

|

Both Github and Gmail are modern web apps, but they have different needs. Github's pages are largely form-driven, with disconnected pieces of data (like a list of branches) that cause a full page refresh; Gmail's actions cause more complex changes: adding and starring a new draft message shows applies the change to multiple places without a page refresh.

Which type of app are you building? Your mileage with different app architectures/frameworks will vary based on what you're trying to achieve.

The way I see it, web apps are a mixture of various kinds of views. Some of those views involve more complicated interactions and benefit from the architecture designed for high-end interactivity. Other views are just simple components that add a bit of interactivity. Those views may be easier and cleaner to implement using less sophisticated methods.

If you never update a piece of data, and it can reasonably fit in the DOM without impacting performance, then it may be good candidate for a low-end approach. For example, collapsible sections and dropdown buttons that never change content but have some basic enhancements might work better as just markup without actually being bound to model data and/or without having an explicit view object.

On the other hand, things that get updated by the user will probably be best implemented using high-end, model-and-view backed objects. It is worth considering what makes sense in your particular use case and how far you can get with low-end elements that don't contain "core data." One way to do this is to maintain catalogue of low-end views/elements for your application, a la Twitter's Bootstrap. These low-end views are distinguished by the fact that they are not bound to / connected to any model data: they just implement simple behavior on top of HTML.

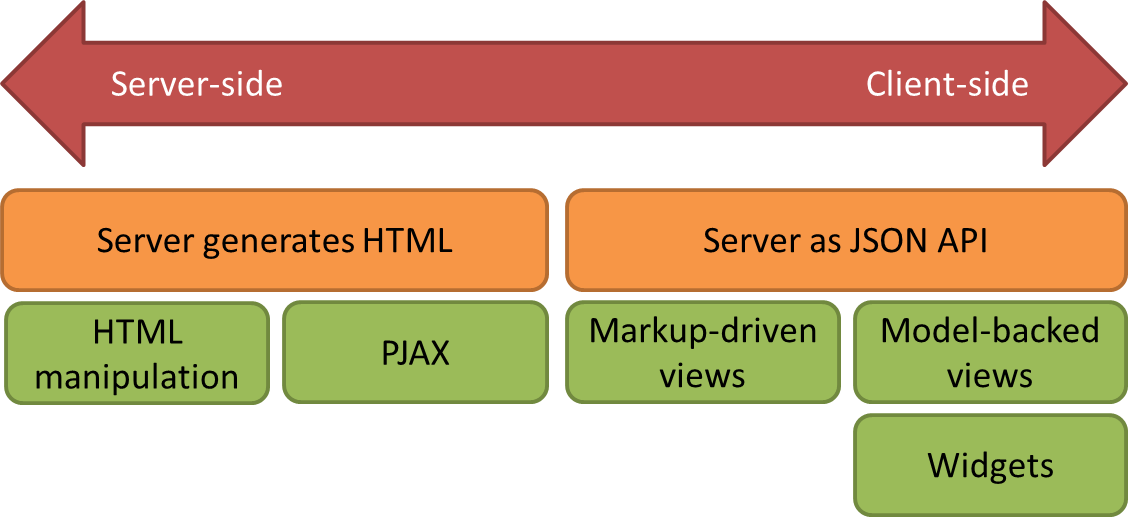

Close to server vs. close to client

Do you want to be closer to the server, or closer to the user? UIs generated on the server side are closer to the database, which makes database access easier/lower latency. UIs that are rendered on the client side put you closer to the user, making responsive/complex UIs easier to develop.

Data in markup/HTML manipulation Data is stored in HTML; you serve up a bunch of scripts that use the DOM or jQuery to manipulate the HTML to provide a richer experience. For example, you have a list of items that is rendered as HTML, but you use a small script that takes that HTML and allows the end user to filter the list. The data is usually read/written from the DOM. (examples: Twitter's Bootstrap; jQuery plugins).

Specific HTML+CSS markup structures are used to to make small parts of the document dynamic. You don't need to write Javascript or only need to write minimal Javascript to configure options. Have a look at Twitter's Bootstrap for a modern example.

This approach works for implementing low-end interactivity, where the same data is never shown twice and where each action triggers a page reload. You can spot this approach by looking for a backend that responds with fully rendered HTML and/or a blob of Javascript which checks for the presence of particular CSS classes and conditionally activates itself (e.g. via event handlers on the root element or via $().live()).

PJAX. You have a page that is generated as HTML. Some user action triggers code that replaces parts of the existing page with new server-generated HTML that you fetch via AJAX. You use PushState or the HTML5 history API to give the appearance of a page change. It's basically "HTML manipulation - Extreme Edition", and comes with the same basic limitations as pure HTML manipulation.

Widgets. The generated page is mostly a loader for Javascript. You instantiate widgets/rich controls that are written in JS and provided by your particular framework. These components can fetch more data from the server via a JSON API. Rendering happens on the client-side, but within the customization limitations of each widget. You mostly work with the widgets, not HTML or CSS. Examples: YUI2, Sproutcore.

Finally, we have markup-driven views and model-backed views.

Markup-driven views vs Model-backed views

If you could choose your ideal case: what should people read in order to understand your application? The markup - or the code?

Frameworks fall into two different camps based on this distinction: the ones where things are done mostly in markup, and ones in which things are mostly done in code.

[ Data in JS models ] [ Data in JS models ]

[ Model-backed views ] [ Markup accesses models ]Model-backed views. In this approach, models are the starting point: you instantiate models, which are then bound to/passed to views. The view instances then attach themselves into the DOM, and render their content by passing the model data into a template. To illustrate with code:

var model = new Todo({ title: 'foo', done: false }),

view = new TodoView(model);The idea being that you have models which are bound to views in code.

Markup-driven views. In this approach, we still have views and models, but their relationship is inverted. Views are mostly declared by writing markup (with things like custom attributes and/or custom tags). Again, this might look like this:

{{view TodoView}}

{{=window.model.title}}

{{/view}}The idea being that you have a templating system that generates views and that views access variables directly through a framework-provided mechanism.

In simple cases, there might not even be a directly accessible instance of a view. Instead, views refer to variables in the global scope by their name, "App.Foo.bar" might resolve to a particular model. Views might refer to controllers or observable variables/models by their name.

Two tracks

These two approaches aren't just minor differences, they represent different philosophies and have vastly different complexities in terms of their implementation.

There two general modern single page app (view layer) approaches that start from a difference of view in what is primary: markup or code.

If markup is primary, then one needs to start with a fairly intricate templating system that is capable of generating the metadata necessary to implement the functionality. You still need to translate the templating language into view objects in the background in order to display views and make sure that data is updated. This hides some of the work from the user at the cost of added complexity.

If code is primary, then we accept a bit more verbosity in exchange for a simpler overall implementation. The difference between these two can easily be at least an order of magnitude in terms of the size of the framework code.

View behavior: in view object vs. in controller?

In the model-backed views approach, you tend to think of views as reusable components. Traditional (MVC) wisdom suggests that "skinny controller, fat model" - e.g. put business logic in the model, not in the controller. I'd go even further, and try to get rid of controllers completely - replacing them with view code and initializers (which set up the interactions between the parts).

But isn't writing code in the view bad? No - views aren't just a string of HTML generate (that's the template). In single page apps, views have longer lifecycles and really, the initialization is just the first step in interacting with the user. A generic component that has both presentation and behavior is nicer than one that only works in a specific environment / specific global state. You can then instantiate that component with your specific data from whatever code you use to initialize your state.

In the markup-driven views approach, ideally, there would be no view objects whatsoever. The goal is to have a sufficiently rich templating system that you do not need to have a view object that you instantiate or bind a model to. Instead, views are "thin bindings" with the ability to directly access variables using their names in the global scope; you can write markup-based directives to directly read in those variables and iterate over them. When you need logic, it is mostly for special cases, and that's where you add a controller. The ideal is that views aren't backed by objects, but by the view system/templating metadata (transformed into the appropriate set of bindings).

Controllers are a result of non-reuseable views. If views are just slightly more sophisticated versions of "strings of HTML" (that bind to specific data) rather than objects that represent components, then it is more tempting to put the glue for those bindings in a separate object, the controller. This also has a nice familiar feeling to it from server-side frameworks (request-response frameworks). If you think of views as components that are reusable and consist of a template and a object, then you will more likely want to put behavior in the view object since it represents a singular, reusable thing.

Again, I don't like the word "controller". Occasionally, the distinction is made between "controllers specific to a view" and "controllers responsible for coordinating a particular application state". I'd find "view behavior" and "initialization code" to be more descriptive. I would much rather put the "controller code" specific to a view into the view object, and make the view generic enough to be reusable through configuration and events.

Observables vs. event emitters

Once we have some view behavior, we will want to trigger it when model data changes. The two major options are observables and event emitters.

What's the difference? Basically, in terms of implementation, not much. In both cases, when a change occurs, the code that is interested in that change is triggered. The difference is mostly syntax and implied design patterns. Events are registered on objects:

Todos.on('change', function() { ... });while observers are attached through global names:

Framework.registerObserver(window.App.Todos, 'change', function() { ... });Usually, observable systems also add a global name resolution system, so the syntax becomes:

Framework.observe('App.Todos', function() { ... });Or if you want to be an asshole, you can avoid typing Framework. by extending the native Function object:

function() { ... }.observe('App.Todos');The markup-driven approach tends to lead to observables. Observables often come with a name resolution system, where you refer to things indirectly via strings. The reason why a global name resolution system - where names are strings rather than directly accessing objects - is often added for observables is that setting up observers without it becomes complex, since the observers can only be registered when the objects they refer to have been instantiated. Since there are no guarantees whether a distant object is initialized, there needs to be a level of abstraction where things only get bound once the object is instantiated.

The main reason why I don't particularly like observables is that you need to refer to objects via a globally accessible name. Observables themselves are basically equivalent to event emitters, but they imply that things ought to be referred by global names since without a global name resolution system there would be no meaningful difference between event listeners and observables with observers.

Observables also tend to encourage larger models since model properties are/can be observed directly from views - so it becomes convinient to add more model properties, even if those are specific to a single view. This makes shared models more complex everywhere just to accomodate a particular view, when those properties might more properly be put in a package/module-specific place.

Specifying bindings using DOM vs. having framework-generated element ID's

We will want to also bind to events from the DOM to our views. Since the DOM only has a element-based API for attaching events, there are only two choices:

- DOM-based event bindings.

- Framework-generated event bindings.

DOM-based event bindings basically rely on DOM properties, like the element ID or element class to locate the element and bind events to it. This is fairly similar to the old-fashioned $('#foo').on('click', ...) approach, except done in a standardized way as part of view instantiation.

Framework-generated event bindings allow you to bind event handlers to HTML without explicitly providing a element ID or selector for the view. You don't have to give elements classes. Instead, you write the event handler inside the markup, and the templating system generates an ID for the element, and tracks the lifecycle of the element (e.g. attached to the DOM/not attached to the DOM etc.), making sure that the event handler is attached.

What update granularity should be supported? View-granular, element-granular and string-granular

This is a subtle but important part of the view layer, since it determines basically how a lot of the rest of the framework code is written.

"Update granularity" refers to the smallest possible update that a particular framework supports. Interestingly, it is impossible to visually distinguish between the different approaches just by looking at code. This snippet:

<p>Hello {{name}}</p>... can be updated at any level of granularity. You actually have to look at framework code in order to know what the update granularity is:

View-granular frameworks allow you to update a single view, but nothing smaller. Internally, the view is represented as a element reference and template function that generates/renders a HTML string. If the {{name}} changes, then you re-render the HTML and change the innerHTML of the top-level element that is bound to the view.

Element-granular frameworks make it possible to update the value directly inside the DOM, but they require that each individually updateable part is represented in the DOM as an element. Internally, elements are added around each updateable piece, something like this:

<p>Hello <span id="$0">foo</span></p>Given this compiled result and some metadata, the framework can then select "$0" and change it without altering the rest.

String-granular frameworks allow you to update any part of the template, and do not require that updateable parts are wrapped inside elements. Instead, they use script tags or comment tags to delimit updateable content (mostly, because the Range API doesn't work on IE). That template might compile into:

<p>

Hello

<script id="metamorph-0-start" type="text/x-placeholder></script>

foo

<script id="metamorph-0-end" type="text/x-placeholder"></script>.

</p>This is almost the same thing as element-granular updates, except that the DOM contains two nonvisual elements for each updatedable part; and conceptually, the framework's binding engine works with string ranges between the two elements rather than with single elements.

What are the benefits and disadvantages of each of these approaches?

View-granular updates mean that a value update causes the inner HTML of each view interested in that update to be re-rendered and inserted into the DOM. View-granular updates are simple: each view corresponds to a single element (and its innerHTML) and only one DOM element needs to be tracked per view. The disadvantage is that since the view cannot render parts of itself individually, doing a redraw might reset things like text in input elements and keyboard focus if they are inside the view markup and in a non-default state. This can be worked around with a bit of coding, however.

Element-granular updates mean that after a view is rendered once, parts of it can be updated separately as long as those parts can be wrapped in an element. Views have bound elements that represent values from some model/data that in the resulting markup are wrapped in framework-generated elements with DOM ids. The disadvantage is that there is much more to track (both in JS and in the DOM), and using CSS is not necessarily straightforward since bound values are wrapped inside elements, meaning that the CSS path to the element is not what you might expect (e.g. p span instead of p).

String-granular updates are the most complex. They provide the same functionality as element-granular updates, but also allow you to specify a bindings that do not correspond to elements, such as a foreach without a container element:

<table>

<tr>

<th>Names</th>

{{#people}}

<td>{{name}}</td>

{{/people}}

</tr>

</table>This could not be done using a element-granular approach, because you cannot insert an element other than a

There are two known techniques for this: <script> tags and <!-- comment --> tags stay in all DOM locations, even invalid DOM locations, so they can be used to implement a string-range-oriented rather than element-oriented way to access data, making string-granular updates possible. Script tags can be selected by id (likely faster) but influence CSS selectors that are based on adjacent siblings and can be invalid in certain locations. Comment tags, on the other hand, require (slow) DOM iteration in old browsers that don't have certain APIs, but are invisible to CSS and valid anywhere in the page. Performance-wise, the added machinery vs. view-granular approaches does incur a cost. There are also still some special cases, like select elements on old IE version, where this approach doesn't work.

Conclusion

The single page app world is fairly confusing right now. Frameworks define themselves more in terms of what they do rather than how they accomplish it. Part of the reason is that the internals are unfamiliar to most people, since -- let's face it -- these are still the early days of single page apps. I hope this chapter has developed a vocabulary for describing different single page app frameworks.

Frameworks encourage different kinds of patterns, some good, some bad. Starting from a few key ideas about what is important and what should define a single page app, frameworks have reached different conclusions. Some approaches are more complex, and the choice about what to make easy influences the kind of code you write.

String-granular bindings lead to heavier models. Since model properties are directly observable in views, you tend to add properties to models that don't represent backend data, but rather view state. Computed properties mean that model properties can actually represent pieces of logic. This makes your model properties into an API. In extreme cases, this leads to very specific and view-related model properties like "humanizedName" or "dataWithCommentInReverse" that you then observe from your view bindings.

There is a tradeoff between DRY and simplicity. When your templating system is less sophisticated, you tend to need to write more code, but that code will be simpler to troubleshoot. Basically, you can expect to understand the code you wrote, but fewer people are well versed in what might go wrong in your framework code. But of course, if nothing breaks, everything is fine either way. Personally, I believe that both approaches can be made to work.